By Lee Valentine Smith – SVT was a San Francisco-based rock and roll band active in the late ‘70s and very early ‘80s. Although they’re probably best remembered for including Rock and Roll Hall Of Famer Jack Casady on bass, the other members of the band were Brian Marnell (vocals), Bill Gibson and Paul Zahl (drums) and Nick Buck (keyboards).

The group definitely had a cool pedigree, with founders Casady – from Jefferson Airplane and Hot Tuna, Gibson – from Huey Lewis and the News, Zahl – of Tuxedomoon, Flamin’ Groovies, and more recently Paul Zahl and the Cat, and prolific composer Buck – fondly remembered as one of Casady’s ‘Tuna bandmates.

Taking their name from Casady’s amp (Super Vacuum Tube) and/or the medical condition known as supraventricular tachycardia, SVT recorded two singles in 1979, an EP in 1980 and one full album, No Regrets in 1981.

One of the first bands signed to San Francisco’s 415 Records, their debut single, “Heart of Stone” was released in 1979. They disbanded in ‘82 when Zahl and Casady left to form Yanks with Jack Johnson and Owen Masterson. Brian Marnell passed away in 1983.

Often cited as one of the best unsung bands of the SF scene, Marty Balin, Casady’s former Jefferson Airplane bandmate, covered the song “Heart of Stone” on his album, Lucky, issued in 1983.

In addition to the fascinating and ongoing Liberation Hall reissues of intriguing SF scene artists, veteran rock scribe Bill Kopp has documented the incredible 415 Records movement in his latest book, Disturbing the Peace: 415 Records and the Rise of New Wave. Published earlier this year by HoZac Books, the engrossing history traces the origins of the label and includes priceless commentary from nearly 100 survivors of the era.

The crafty folks at Liberation Hall Records are keeping SVT’s legacy alive with Always Comes Back, a new double-vinyl version of the label’s CD counterpart. The disc included all 21 of the tracks from singles, an EP and album and the vinyl version features three more songs that didn’t appear on the CD.

The bonus tracks, from the earliest recordings of the group include “Snow Gorilla,” “Sex Attraction” and “How Could You Ever.” The songs were officially credited to The Jack Casady Band, as the group was briefly known, before the wise switch to SVT. Die-hard completists should also grab a copy of The Price of Sex, a newly issued DVD that features a trove of archival footage of SVT.

Recently, I spoke with Jack Casady just before he joined longtime bandmate Jorma Kaukonen in support of Hot Tuna’s 50thanniversary Burgers tour. I also tracked down busy composer Nick Buck by phone from his home in California – as well as journeyman music documentarian Bill Kopp at his office in Asheville, North Carolina. After all, he literally wrote the book on the scene.

–

Jack Casady:

The pandemic delayed the vinyl pressing of the SVT collection and of course, touched us all in many ways. How are you doing during these crazy times?

I was just talking to Jorma about the fact that even just about a year ago, we realized how fortunate we are to be able to keep playing music in these times. So I think the real thing that came out of the pandemic, for both of us anyway, was a chance to really delve back into the techniques and intimacies of practice on our own instruments. Usually, life and touring interfere with any sort of consistent practice. You do it the best you can later in your career. Of course, early on in your career, that’s all you’re ever doing. So it’s really been a blessing in disguise for us. We went over a catalog of 150 songs and it was really good in that sense. But yes, it’s nerve-racking – the financial issues and the fact that people work for you – so it’s hard to keep paying everybody’s incomes and everything else. But all in all, compared to some other people, we fared through the pandemic pretty well, I think. Like everybody else, we’re using our savings to live on with no real new money coming in, but things are starting to get back on track again. I’ve got to say that I’m never one to complain too much. I mean, you bitch and moan about certain stuff but mostly there was so much happening on a more tragic level than mostly our concerns were with our own family issues. You know, Jorma’s got a 15-year-old daughter. He’s 81 with a 15-year-old daughter. She’s just learning how to drive and trying to keep everyone healthy in their family. So there’s a lot going on in both of our lives to deal with – in order to just stay alive and healthy.

That brings us to the incredible new SVT record. I am so glad it exists and listeners finally have a chance to experience the music – maybe for the first time in their lives. Let’s talk about the process of the band for a moment. In the liners, the poster reproductions advertise “the Jack Casady Band” – obviously SVT started out with that name. Musically, where were you at that time, to want to create something so vastly different than your previous body of work?

Well, you know, Jorma and I had first played together in high school, in 1958, in a cover band. It was rockabilly stuff and whatnot. Then, when I joined him – at his request – out in California in ’65 to start the Jefferson Airplane, that band ran through 1972. Simultaneously, we were doing a lot of playing. I mean, we were on the road, either with the Jefferson Airplane or Hot Tuna for years. When we decided to pull the plug on Jefferson Airplane in ’72, we kept on going as Hot Tuna and did a lot of touring. But by that time, we were just trying to find some ways of not killing ourselves. So many of our friends had died of various drug overdoses and lifestyle choices and whatnot. So Jorma and I actually got into speed skating. We started closing Hot Tuna down in the wintertime and going off for two, three months at a time to Europe and just training and skating. Not world times, just amateur, but still it was a new discipline to get away from what was going on in the States. Then we’d come back over here and play.

That was an incredible time for Hot Tuna, a very prolific period.

We released a lot of great albums through that period of time, yeah. But then a couple of things happened – I think, pretty much all at once. The record company wasn’t going to resign us, I believe, for another record at the end of ’78, ’79. So we thought about the best way to do it. We had never not played together, pretty much since 1965. We’d just been there together doing all these projects. I think Jorma felt it was time for a break – and there were some personal issues going on in his world. So we stopped playing. During that time, I was looking around. The musical styles were changing, as you know. Things were shifting around a little differently from the way it had been before. But we were still young, still searching for a lot of different stuff to do. I think at that time, I’d asked a lawyer friend of mine who was famous in the music business, if he’d heard of any talented new players out there. He played a few tapes of different people and he had this tape. It was a cassette tape of Brian Marnell playing with one of his bands on a demo he’d made.

What was your initial reaction?

He had a really interesting energy and aggressiveness, but he also had a good sense of songwriting. Pop songwriting. But Brian was never a lyricist for deep social change, so to speak. His songs were mostly about his girlfriend at the time. In any case, the energy on the guitar was in a different direction than I’d played with Hot Tuna or with Jefferson Airplane. But I had an eight-year career before I came out to California to start the Airplane, playing in a lot of rhythm and blues bands and a lot of different styles of music – from country to jazz and all kinds of things. So I was already open to all types of music.

And you were looking for something new and interesting.

Yeah, it just appealed to me to try to get a different angle into playing music. A lot of the new wave and punk stuff going on was more stripped-down music. I read that as less extended solos and jams and things like that with more short, aggressive, intense songs. I sort of dove into that world for a while. When I listen back to this record in retrospect now, of course, I think I still sound like Jack. I’m doing plenty of melody work and whatnot. But I’m peddling a little more in the playing. I wanted to shake up my approach from a lot of the two-finger melodic playing I’d done, into just a little something different. I even started playing with a thumb pick, as well as the two fingers, in order to get a more aggressive downbeat style from a bass player’s point of view. But again, when I listen back to the stuff now – in my perception, of course – I think the music still comes out sounding like Jack.

So the band became a bit of a new challenge?

That’s right. But I think what I enjoyed about Marnell’s songwriting was it gave me a completely open opportunity to craft bass work without any preconceptions, so to speak, and try to attempt it that way. So I asked Nick Buck to join me in that effort. He had played with us in that last section of Hot Tuna in ’78, ’79, as we started this out. Then I asked Marnell if he knew of a drummer, and he knew Bill Gibson. Of course, a year later, he went on and became quite famous with Huey Lewis and the News. But Marnell and Bill and Huey Lewis and the News all went to Marina High School and were all of the same generation. They’re all 10 years younger than me. So we started playing and working on songs together. Because we didn’t have a name yet, we went out and booked some shows right away to get some material fleshed out. Of course, we used the Jack Casady Band to get a bookings. Then later on we came up with the name SVT, which was actually after my amplifier. Somebody pointed out later on that it was also the initials of a heart condition called supraventricular tachycardia, which wasn’t quite as catchy in the promo world. Then Bill left after a year to join Huey Lewis. Paul Zahl joined us and we continued on with Nick Buck. About a year later, Nick dropped out and we continued on for a couple years as the trio. So those are the guys on many of those cuts on that released album, as well as the earlier stuff. So you’ve got a good cross-cut of whole the three-year existence of SVT.

It’s a nice little photograph of the era.

It is interesting. And naturally in San Francisco, we played the Mabuhay quite often. But it was tough. It was tough to get out there and get recognized. Either my name was an albatross to them because they were younger and wanted their own identity or it was just tough to get bookings. Naively you think, oh well, because of who you are, all of a sudden you have a new band that’s going to make it. But like any band, you’ve got to pay your dues and see if you can get any actual fans to listen.

With your legacy, how did that approach work? You’d already played Woodstock and on a ton of major-label releases.

I think in the beginning, the band alienated the Hot Tuna fans. And of course, in the younger punk world, they weren’t quite sure about a 10-year-older guy in a band that identified with the era of the time. But San Francisco is a forgiving city and a unique town, so we held our own there. We also did some touring and managed to get a pretty good fan base. But then during that time, it was a tough drug period on some people. Of course, Marnell unfortunately and tragically paid the price on that.

But for you personally, was it exciting to be basically starting over with a new project and all the expectations that inevitably come along with it?

Well, it was excitement with frustration. But yes, musically, I really believed in the band. I gave it my all, like I do with anything. I always try.

At the time, what were you calling the SVT music? It was very energetic, very powerful, but it wasn’t exactly pop.

I guess I could call it good songs. But it’s guys like you that have to call it something. To me, it’s songwriting and music at the time and of the moment. You go in, you write your songs, you walk in and you do it. Marnell certainly wasn’t trying to write in a certain style. Now, he did have his influences. They were immediate. Of course, he was a young writer at the time, so they would show up in different songs from different things he’d heard. I wasn’t prepared to label it as anything at the time. That’s part of what’s hard to do when you’re writing stuff like that. There are some people that write for a genre, but we weren’t.

You mentioned it was tough at times. Obviously you had to build an audience and all that sort of ‘new band’ stuff. What was the San Francisco scene like at that time – from your point of view?

Well, the scene – it’s interesting. I look back on it now with a different viewpoint than at the time, because as you’re going through your 20s and 30s and there I am in my 30s, and music styles were changing. And as they changed from the ’60s into the ’70s with the disco and all that, now they’re moving into new wave and punk toward the ’80s. Shifts in styles of what will be played, what’s perceived to be old style, and what’s perceived to be ‘new’ by the next generation, all that comes along. With all of that, there’s a certain anxiety; ‘Is anybody going to like this or not like this?’ That’s part of the business in that. Because you’re not quite as young, naive and stupid as you were in your 20s. As you gain wisdom though, you gain a certain amount of trepidation along the way, too. But you believe in yourself and venture forth. Like any new sport team, you’ve got a player that leaves one team and enters into another and he’s got to work his way through that team, you know?

Since you mentioned the culture changes, I’ve noticed it seems with every decade, there’s a major shift of sorts. Like between ’69 and ’70, there was a big shift, obviously. Then between ’79 and ’80, there was another big shift.

Yeah, absolutely. Absolutely. But are you talking about with years or age?

No, in general. At that point, everything was changing. Culture was changing, fashion was changing. Things that were cool a few years previous were quickly sidelined for people of every age.

That’s right. I think for any artist, I mean also actors or anybody in the art field, those ages make a big difference. When you’re leaving your 20s and going into your 30s, that’s one thing. Then 30s going into 40s is another thing altogether. You are no longer the new generation with the cutting edge, so to speak. And you never will be again. But later on, you broaden as a human and you don’t identify with just the peer group that you necessarily grew up with. In our case, for instance, Hot Tuna – we’ve always had a great fan base. But as you get older and in your 50s, 60s, 70s or even 80s, your fan base actually broadens and everybody’s okay with it. If you’re playing the kind of music that’s true and real and reflects who you are in that moment on stage. That’s what we do with Hot Tuna, with Jorma and I. So music can be a bit amoeba-like, it reflects who we are and the men we are today and the maturity we have today. We’re not wearing spandex on stage, trying to pretend we’re 20 and hunting girls, you know?

That mindset obviously applied to SVT.

Right! With SVT, the main approach for me was musical and trying to contribute what I’d learned of music. My goal was to add some more movement and melody in the bassline in a world of punk / new wave style where mostly people were just thumping on the bass notes for a drone. It was kind of like disco was, in a way, before. The bass players were certainly playing cool stuff in disco, so things move around. You’re putting different genres together. So, whether we liked it or not, what we were doing was marrying two generations together – or two half-generations together – to see how it would work out. We didn’t ever really reflect upon it like that, like we’re talking about it today. We just got in a room together and made music.

That seems to be your career work ethic.

Well, yeah, I think you need to look at it that way. Any artist needs to be true to the craft. You don’t want to find yourself gritting your teeth the whole time, saying, ‘I’m playing something just for the paycheck.’ Because there was definitely no paycheck with SVT.

But the one constant I’ve seen, throughout your entire catalog, is the Hot Tuna project. That’s the only thing that seems to be a running thread through your considerable body of work.

Right. Well, you know we’re about to play Carnegie Hall next week, and it’s already sold out. And we’re doing some residencies in this coming November and December. We sold out the Capitol Theater. My picture’s up on the wall at the Capitol with Jorma next to me when we played there in 1970 with Jefferson Airplane. So it’s quite an amazing thing for us to continue. During the pandemic, Jorma posted 50 concerts up on his Fur Peace Ranch site [www.furpeaceranch.com]. I came out and posted maybe 10 or 12 with him. We kept playing and spent two, three months together, working on material and playing and just enjoying what we do – until we could get back out and play shows again. We just keep going.

That’s because you’re always creating something, whether it’s a new style or a fresh continuation of your own style.

Yeah. But it’s not just style, I think of myself as a musician. I just happen to play the bass. When I’m working with Jorma, we work on so many things. We get a chance to play interesting pieces of music that can fluctuate inside the music. So the interpretation is very valid each evening. We try to make every evening special. I’m just not interested in the one that’s already done. My duty as a musician and for Jorma, too – is for us to get in the moment and listen to each other on stage and play off that. He’s not playing a guitar part. I’m not playing a bass guitar part. We’re just interpreting the music. We’re playing the song and interpreting the music. That’s how we’ve always done it.

That’s perfect. But what’s next that you haven’t done that you still want to do?

Well, I don’t think I look at it that way. To me, it’s a flowing thing – any more than a painter isn’t satisfied with just one painting. You move on. You reflect on the day’s living and the day’s influences, then you see what’s up around the corner. But it was really an enjoyable and fascinating period of time, those three years that we were together like that for SVT. I must say, God bless Brian Marnell. I’m sorry to say he’s not here today. I’d love to hear what he’d be doing today.

His spirit definitely lives on in this new album. So thank you for being a major part of it.

Well, thank you very much and thanks for talking to me about it all.

–

Nick Buck:

The SVT collection is a great piece of music history.

It is and I think that’s why we labeled it the ‘authorized recordings.’ We took a lot of care to put out the right music, thank all the right people and document all the details that were somehow sketchy. I think it’s a pretty comprehensive body of work.

It’s a nice conduit between different styles and eras in culture and music. How did the project happen?

It was very interesting how it all came about. I received a call, let’s see, in the early part of COVID, maybe like January or February of 2020. There was a gentleman in Los Angeles who was working in film and TV, trying to reach me to license, potentially, the SVT material and any material that I had. So I called Howie Klein and I asked him, ‘Is this guy legit?’ He goes, ‘Yeah, the guy’s legit, you should contact him.’ And he said, ‘Besides, there’s another gentleman on the East Coast by the name of Arnie Shore who runs a record label. He’s interested in talking to you about some stuff that’s going on, too.’ I obviously made connections with both guys. We started on with the Disturbing the Peace piece, that was the first one, and right on the heels of that he said, ‘I want to start working on a compendium of all the SVT stuff. Since the CD has time limitations, what we’ll do is we’ll put out X amount of material on the CD. We’ll leave X amount of material being digital bonus tracks. Maybe eventually if it works out, we’ll release a vinyl record.’ And now here we are! We actually mastered this from vinyl. I have a guy that’s a physicist at University of California, Berkeley, and he was able to work wonders on the vinyl masters. We had pristine, clean vinyl and we made the masters. Then I worked on the graphics to make sure all the details were right on the initial CD package. The goal was to make it a clean representation of what the band was and is.

I notice you have a couple of composition credits on the bonus vinyl tracks.

Yes, exactly. I had, let’s see, “Sex Attraction,” which was a club favorite that just somehow never made it to vinyl while I was in the band and then we have “Snow Gorilla” which was a holdover, an instrumental we played in Hot Tuna. We gave it a different treatment and it’s got a lot of Jack’s signature playing on it, which is a lot of feedback tones and some of the sounds he’s known for. That’s a really great piece of the vinyl record.

From your perspective, how did SVT come about? Obviously, you were already playing with Jack in Hot Tuna, but it seems that Jack was looking for something new to do.

Right. Well, when we ended Hot Tuna, Jorma went off to Europe to speed state. Jack and I were left alone in Marin. We got together and chatted, did some playing and then he started pulling through some tapes, looking for players from tapes that were sent to him by a gentleman he knows called Brian Rohan. He found a tape a band called Sound Hole. It was interesting, the singer was good, the band was tight. So we went to see them at a showcase, I forget exactly the venue, maybe it was Uncle Charlie’s. We went to see them at this ostensibly pivotal moment in their career to be signed as their own entity. But Jack liked Brian and it looked like a great thing, so we kind of made short order of it. Brian agreed to come on board and Bill followed suit. So that’s how it goes. Then we were able to cobble together rehearsal space at different places. Nobody had any real money but we started rehearsing and playing. We made our own gig posters for the first few gigs as the Jack Casady Band. I made those pretty much by hand myself. Marnell’s girlfriend’s father was an amateur photographer. He took a photo of the band, so we used that and we went on our own and just started doing it as a kind of a do it yourself thing. We were getting some gigs with Jack’s name, by calling it the Jack Casady Band, but we were doing pretty much everything else ourselves. That’s pretty much how it all started.

At that time what was his position in the scene? Were people coming to the gigs because the bassist was in the Airplane and Hot Tuna?

Yeah, you’re bringing baggage, so it has an inherent sense of worth. If he has lineage with those two bands and you think you’re going to go hear that kind of music, then you potentially could be disappointed. Unless you understood the evolution and the increase in the energy. We had people come along and yell for Tuna material, and there would be people coming along having heard from friends or something about what the band actually was about. So there was this kind of bifurcation of the audience. Some people wanted to hear us, some people wanted to hear the Jack of old. It evolved over time that people accepted us for what it was. But in the smaller punk venues, Jack didn’t really carry the weight you might have thought he would. We would go to some venues and there would be Hot Tuna fans and Airplane fans screaming for that type of music. But the little punk venues were filled with people looking for that new sound, that different sound, and we became one of those bands. In many ways, we were just another band on the scene. So we just kept evolving. It could have gone on for a while. It was very interesting for a while. And then, when Brian passed, any hope of an SVT reunion was closed. And that’s just what happened. The scene had gotten pretty heavy.

–

Bill Kopp:

Like Always Comes Back, your book Disturbing The Peace, is an impressive document. You literally documented an entire scene – and that is no easy task.

It was just a blast to do. It was so much fun and I’d like to think I’d made quite a few friends from doing the interviews and research. Some people, I would talk to over and over again to get all the information. So it was cool, especially as an outsider to the scene. I was living in Atlanta when that stuff was happening, working at Turtle’s Records. But I knew about some of the stuff that was going on and I visited San Francisco around that time – though I certainly wasn’t directly a part of the scene. But I kind of feel like I got about as close as you could get without having been there. That was my goal with the book, to basically do right by everyone who was involved in the story and to bring it alive for anybody who wasn’t and might interested in the history.

Right. In a way, it’s actually good that you weren’t immersed within that scene because of all the politics that go along with an artistic community.

Exactly. There’s such a thing as being too close to it, you know? Yeah and you’re talking to people about things that happened 35, 40 years ago. …and it was the eighties, so there’s that side of the equation.

Let’s talk a bit about SVT in particular.

Well, as I’ve mentioned before, when I was writing the book, SVT was the band usually mentioned as the Bay Area’s most deserving band for greater success. Much better than they found during their short few years together. They were a really good band – with a sound that included new wave, punk and early power pop. The fact that SVT featured the extraordinarily talented Jack Casady on bass meant that they were muscular, tuneful and incredibly compelling. They shoulda been contenders, right? Unfortunately, even though they did tour a bit, they never really grabbed the attention of a wider audience outside of the San Francisco scene.

They’re definitely obscure, but the music is undeniably great. The fact that a little band contained a guy who’d already played Woodstock and on a number of influential recordings makes the story even more interesting.

Oh, sure. And it was more than a busman’s holiday of sorts for Jack Casady. I mean, as you know, as he explained it to me and I’m sure he told you as well, he Jorma had been playing together since they were kids, a long time before the Airplane. It’s not like they had some falling out or anything when they took a bit of a break. For him, taking a break didn’t mean not to play music. It meant just doing something else. I think he was just ready to flex his musical muscles a bit and do something new. I think he wanted to apply his creativity and his talent to something that was substantially different.

Listening to the recordings, it appears SVT’s sound evolved quickly.

It really did. It’s certainly interesting. If you listen to the last couple of tracks on the new comp, from when they were actually called the Jack Casady Band, they don’t really sound like what could quickly be known as their so-called ‘signature sound.’ It’s a rare look at an enormously talented band, trying to figure out how it wants to sound. When they did find that sound, they did some really, really good music in a very short period of time. They were fairly unique among the early 415 label bands in that they did tour; they got outside the Bay area a bit. The whole SVT story is just an incredible moment of time. They burned brightly, briefly – and left an incredible legacy. So really, what more could you ask from any band?

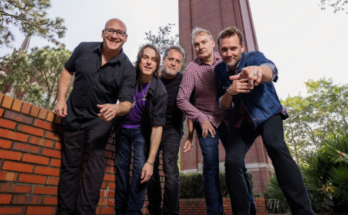

Cover Photo © Charly Franklin